On building systems that still fail

It was the year 1991. Fernando J. Corbató received the Turing Award, and he published the lecture paper On Building Systems That Will Fail.

In the year 2019, systems still fail, and there are so many things we can learn from the past.

In this paper, the author talks about systems that he helped to design and build during the sixties (CCTS, Multics). When designing “ambitious systems”, as Fernando describes them, the question to ask is not if something will go wrong, but when it will go wrong, because ambitious systems never quite work as expected.

He later gives good reasons for that. Most system’s failures are caused by subtle mistakes that are very difficult to avoid and to some extent are inevitable.

Ambitious (or complex) systems have some general properties:

- They are often vast and have significant organizational structures going beyond that of simple replication.

- They are frequently complicated and are too much for even a small group to develop.

- They are pushing the envelope of what people know how to do, and as a result there’s always a level of uncertainty about when completion is possible.

- When they work, they often break new ground, offer new services and soon become indispensable.

- By having opened up a new domain of usage, they invite a flood of improvements and changes.

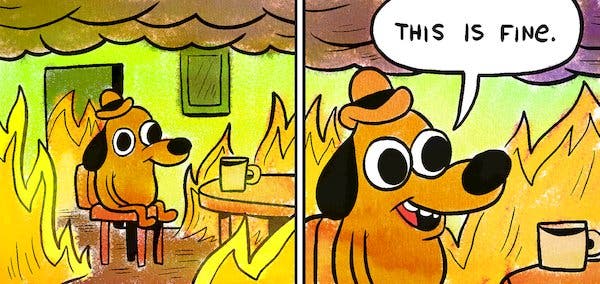

But ambitious systems aren’t only difficult the first few times. Almost 30 years after the publication of this paper, and more than fifty years after the development of CCTS and Multics, we can’t get them right., and a key reason for that is change.

The expression “building the plane as you fly” has been used to describe how those systems are designed and built. And most of the time it is not because a lack of planning, but because it is impossible to anticipate how a system will evolve, and the complexity of the tasks involved in designing an ambitious system makes it almost impossible to build it correctly the first time.

Another problem (if you have this problem you’re probably doing the right thing) when developing a successful ambitious system is that people get used to it surprisingly fast. As Fernando says in the paper when talking about CCTS:

[…] users who had been enduring several-hour waits between jobs run under bacth processing were suddenly restless when response times were more than a second. […] It seemed like the more we did, the more users wanted.

And I guess that a lot of developers can relate.

Fernando also says that when you have a multitude of novel issues to contend with while building a system, mistakes are inevitable. What he means here is that when a system grows and evolves in ways that were not anticipated, early design decisions can create unexpected issues. Design bugs are often subtle and occur by evolution with early assumptions being forgotten as new feautres ir uses are added to systems.

Scaling systems and organizations go hand in hand. When new layers of management are introduced in an organization, the top-most layer become out of touch with the relevant bottom issues. On top of that, large projects encourage specialization, so only a few team members understand all of the project.

And when systems scale and grow, security issues arise. But there’s no way to simply look at the system and determine what the privacy and security implications are.

The paper finishes with the author given some interesting take aways:

- Simplicity and elegance are not only important but necessary. Simple and elegant systems are easier to reason about.

- The value of metaphors should not be underestimated. Metaphors help us to understand hard concepts at a higher level. We don’t need to understand all low-level details of a complex system.

- Use of constrained languages for design or synthesis is a powerful methodology. If everybody speaks the same language, errors are reduced.

- Anticipate human usage errors as much as hardware failures.

- A system will have to be repaired and modified. Design with that in mind.

- Share knowledge in the team. Increase the bus factor.

- Learn from past mistakes, but be alert to the possibility that new circumstances (or even old ones) require new solutions.

But as Fernando says, the general problem with ambitious systems is complexity. Don’t wonder if something will happen, but rather ask what one will do about it when it does occur.